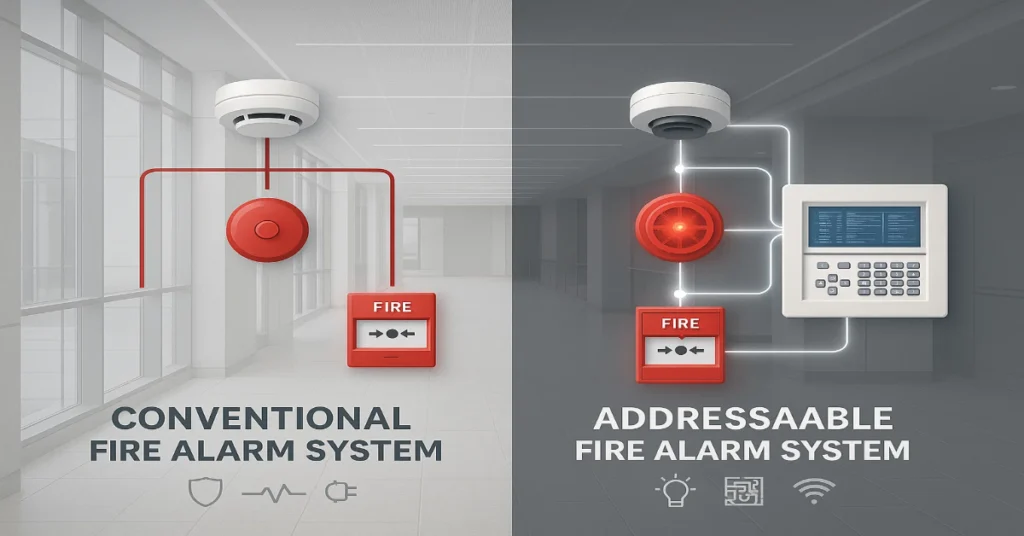

Fire alarm systems come in two basic types: conventional and addressable. In a conventional system, detectors and pull stations are wired in separate circuits or zones and the control panel simply indicates which zone has an alarm.

An addressable system, by contrast, communicates with each device individually. Each detector or module has a unique address. When a sensor is triggered, the panel pinpoints the exact device and location.

In practical terms, conventional panels give only zone information (e.g. “Alarm in Zone 3”), whereas addressable panels report precisely which detector went into alarm (e.g. “Smoke Detector 4.23 – Warehouse, Aisle 3”).

This guide on addressable vs conventional fire alarm systems explains how each works, highlights their pros and cons and helps industrial managers choose the right solution for their facility.

Conventional vs Addressable Fire Alarm Systems: Working

| Feature | Conventional Fire Alarm System | Addressable Fire Alarm System |

|---|---|---|

| System Layout | Building divided into zones; each zone has its own circuit wired back to the main panel. | Devices wired in loops (circuits go out and return to panel). One loop can support dozens or hundreds of devices. |

| Wiring Method | All devices in a zone share the same pair of wires; requires multiple “home-run” circuits. | Only two wires per loop (out and back). Less cabling overall. |

| Device Identification | Panel shows only the zone in alarm (e.g., “Zone 2 – Second Floor East Wing”). Cannot identify the exact device. | Each device has a unique digital address. Panel shows the exact detector and location (e.g., “Smoke Detector 04-23 – Warehouse, Aisle 3”). |

| Supervision Method | Analog supervision with resistors to monitor voltage/current changes. Detects alarms or open circuits. | Digital communication. Panel continuously polls devices and receives real-time status updates. |

| Response Process | Responders must manually search the indicated zone to locate the exact source of fire. | Responders know the precise location immediately, speeding up investigation and evacuation. |

| Fault Detection | Limited to showing “trouble” if a circuit is broken or shorted. Requires manual tracing. | Devices can report their own faults (e.g., dirty sensor, wiring issue). Isolation modules keep rest of system active if one section fails. |

| Installation Effort | High – extensive conduit and copper wiring required. Each device wired directly to the panel. | Lower – fewer cables required. Adding devices is easier since they join the existing loop. |

| Panel Complexity | Simple, inexpensive control panel. Limited functions. | More sophisticated panel with microprocessors, digital display, and advanced programming. |

Conventional vs Addressable Fire Alarm Systems: Pros and Cons

| Aspect | Conventional Systems | Addressable Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Pros | – Time-proven and simple design. – Devices and panels are generally less expensive. – Straightforward panel logic; minimal programming needed. – Effective for very small facilities (single-story, few rooms). – Zone-level information is adequate in low-rise, easy-to-check buildings. – Basic troubleshooting (resistors, detector swaps) can be done by any technician. | – Provides precise location of each activated device. – Continuous device status reporting improves emergency response. – Supports advanced features: section isolation, adjustable sensitivity, automatic trouble checks. – Fewer false alarms due to device-level diagnostics. – Efficient loop wiring reduces conduit and labor costs. – Easy to expand by adding devices to existing loops. – Scales well for large or multi-story facilities. |

| Cons | – Limited information: only identifies the zone, not the exact device. – Slows emergency response in large facilities (technicians must search entire zones). – More prone to false alarms: any detector issue triggers the whole zone. – Maintenance is more labor-intensive (must check multiple devices after each alarm). – Wiring is intensive: each device must be home-run to the panel. – Modifications or expansions require costly rewiring. – Limited panel zone capacity; growth may require new panels or boards. | – Higher cost per device and panel due to advanced electronics. – More complex commissioning: each device needs programming and labeling. – Longer startup and configuration time. – Requires specialized training for technicians. – Repairs can be expensive; replacement components may be brand-specific. – Higher upfront investment may not be justified in small installations. |

Conventional vs Addressable Fire Alarm Systems: Cost Comparison

| Category | Conventional System | Addressable System |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Installation | – Cheaper hardware (basic panels & detectors) – High labor cost due to extensive wiring for each zone – Estimated $0.75–$1.25 per ft² | – More expensive hardware (advanced panels & devices) – Lower labor cost thanks to lighter loop wiring – Estimated $1.00–$3.25 per ft² |

| Maintenance Costs | – Higher labor costs: technicians must manually check zones and wiring – Troubleshooting wiring faults can be time-consuming – Cheaper, widely available replacement detectors | – Lower labor costs: self-testing and digital reporting simplify inspections – Fewer false alarms due to sensitivity control – Replacement parts (detectors/modules) are costlier and often brand-specific |

| Long-Term Value | – Zone-based alarms may trigger unnecessary sprinkler activation, causing costly water damage – More false alarms → downtime and fines | – Precise detection can limit sprinkler activation to local area, reducing damage – Fewer false alarms → less downtime and fewer penalties – Often pays for itself over time in large/complex facilities |

Conventional vs Addressable Fire Alarm Systems: Installation Complexity and Scalability

| Factor | Conventional System | Addressable System |

|---|---|---|

| Wiring Method | Each zone requires a separate cable run back to the panel (home-run wiring). | Devices share a common two-wire loop run out and back to the panel. |

| Labor Intensity | Labor-intensive; multiple circuits mean more conduit, cable, and terminations. | Less wiring required; a single loop can cover multiple areas, saving labor and materials. |

| Device Capacity per Circuit | Typically limited (about 20–24 devices per zone per NFPA guidance). | High capacity; panels can often support 99–128 devices per loop. |

| Expansion Flexibility | Limited; adding new devices often requires running new circuits and using additional zone slots. | Flexible; new devices can be added by connecting them to the loop and assigning an address. |

| Modification Effort | Difficult; rewiring usually involves shutting down the system and pulling new cables through ceilings/conduits. | Easier; expansion usually just requires programming new devices and possibly extending loops. |

| Scalability | Poor scalability; growth may require new panels or major rewiring. | Excellent scalability; ideal for facilities that plan future expansion or retrofits. |

| Technical Setup | Simple; no device addressing required; just wiring into zones. | Requires programming; each device must be assigned a unique address. |

| Fault Tolerance | A single wire break can disable an entire zone. | Loops often provide redundancy; isolator modules help contain faults to small sections. |

Regulatory and Compliance Considerations

Both system types must meet fire and electrical codes. In the United States, NFPA 72 (the National Fire Alarm and Signaling Code) sets performance and installation standards for all alarm systems.

Notably, NFPA 72 does not mandate one system type over the other. It allows any listed (UL-approved) system that satisfies the building’s fire protection requirements.

However, components must be listed. All fire panels, detectors, modules and wiring must be approved to NFPA 72 standards (e.g. UL 864 for control units, UL 268 for smoke detectors). OSHA regulations also apply in industrial workplaces. OSHA 29 CFR 1910.165 requires that employee alarm systems be “approved” and remain operational.

In practice, this means fire alarm control panel equipment should carry a UL (or equivalent) listing. Wiring must comply with NFPA 70 (the National Electrical Code) or local electrical codes. As one industry source observes, “cabling for these systems is governed by the NEC and the units themselves should be UL approved”.

In addition, local authorities often demand certified installation and testing. For example, the Ontario (Canada) Fire Code requires that alarms be installed, inspected and maintained by qualified professionals.

Industrial environments may impose further requirements. Hazardous areas (with flammable liquids, dust or gases) might need explosion-proof detectors and special wiring methods. While either system type can use those specialized devices, the design must account for them (for instance, planning loop segments through classified zones).

Emergency notification (sounders, strobes) must also meet any venue-specific mandates (e.g. OSHA requires alarms to be perceptible above ambient noise). Regular testing and maintenance are required under NFPA 72 (typically annual inspections of the whole system) and by OSHA. Addressable systems often provide built-in tools (like electronic questionnaires and history logs) to help satisfy these inspection requirements.

In summary, neither system offers a compliance shortcut. Both must meet the same performance and safety standards. Building managers should work with code experts and fire marshals to verify that the chosen system configuration fulfills all industrial fire safety regulations.

Choosing the Right System for Your Industrial Facility

The best choice depends on the size, layout and needs of the facility, as well as budget considerations. The key factors include building complexity, required information level, expansion plans and specific risks. The table below summarizes typical recommendations:

- Small/simple facilities: For a single-story warehouse or a small workshop, a conventional system may be adequate. In such cases, the lower hardware cost and simplicity can offset the extra wiring. If the area is compact and easily searchable, zone-level alerts may be tolerable. Conventional systems have lower up-front costs, making them attractive when budgets are tight.

- Large/complex facilities: Factories, multi-story plants, large storage buildings and similar complex sites usually favor addressable systems. Digitize Inc. notes that buildings such as factories or schools “benefit from the precise location tracking” of addressable alarms. When fires must be found quickly among thousands of square feet, knowing the exact detector accelerates evacuation and firefighting. Addressable systems also easily integrate into modern building management. For example, linking alarms to emergency ventilation or remote monitoring which is valuable in big facilities. Safe and Sound Security explicitly cites industrial buildings as a prime addressable application.

- Expansion and modularity: If the plant is likely to expand or change frequently (adding new equipment areas, renovations, etc.), addressable systems are generally better. You can simply add devices or loops without re-engineering the whole system. Conversely, a legacy plant with a fixed layout might stick with conventional panels, especially if retrofitting new technology is very disruptive.

- Special hazard zones: Facilities with areas of high risk (e.g. chemical processing rooms, spray booths, engine rooms) often require more sophisticated detection (like linear beam detectors or aspirating systems). These advanced devices are typically addressable by nature. If the industrial process produces factors that can cause false alarms (dust, steam, smoke), an addressable system with adjustable sensitivity can help avoid nuisance trips.

- Redundancy and reliability: In mission-critical industries (power plants, refineries, high-value manufacturing), addressable systems’ ability to self-test and provide detailed status is a major plus. The ease of isolating faults (loop segments) also adds resilience. Conventional systems have fewer electronic parts, but their single-point zone faults (like a shorted wire) can disable entire areas.

- Cost vs. benefit: Finally, if initial budget is a dominant concern, conventional panels might be chosen for small operations. However, managers should weigh long-term costs: false alarm penalties, unscheduled downtime and fire damage can far exceed the savings on initial equipment. As one guide observes, advances in addressable technology “can save more lives” by sounding alarms intelligently and should not be dismissed for cost reasons.

In many cases, a hybrid approach or a wired/wireless combination might also be considered. Some manufacturers offer hybrid panels (using addressable-style monitoring on conventional loops), but these often sacrifice the full benefits of each type.

Wireless devices can be added in hard-to-wire spots, but building managers must ensure wireless communications are reliable in industrial environments (thick walls or interference can be an issue). Any non-traditional technology must still comply with the same listing and performance requirements.